And while Pfizer’s vaccines are already flowing to Britain, Canada and the United States, it is unclear when they will arrive in other countries. Mexico, according to an announcement, could get its first vaccines any time in the next 12 months.

Clemens Auer, a chief negotiator for the European Union, said an in an email that its contract with Pfizer for 200 million doses came with a “fixed delivery timetable,” but that he was keeping the details from the public. “Details don’t matter much,” he said, given the high volume of promising vaccines the E.U. had secured.

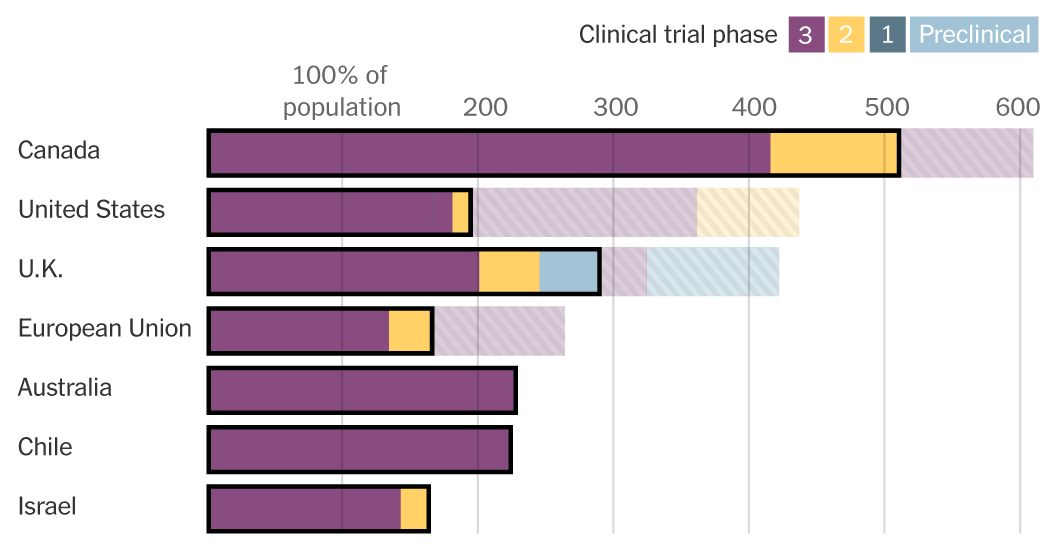

In Canada, the government has faced questioning over its contract with Moderna. The country secured an agreement in August for 20 million doses, with an option for an additional 36 million. The United States announced a deal for up to 500 million doses shortly after, and Britain and the European Union announced their own deals last month.

The Road to a Coronavirus Vaccine ›

Answers to Your Vaccine Questions

With distribution of a coronavirus vaccine beginning in the U.S., here are answers to some questions you may be wondering about:

-

- If I live in the U.S., when can I get the vaccine? While the exact order of vaccine recipients may vary by state, most will likely put medical workers and residents of long-term care facilities first. If you want to understand how this decision is getting made, this article will help.

- When can I return to normal life after being vaccinated? Life will return to normal only when society as a whole gains enough protection against the coronavirus. Once countries authorize a vaccine, they’ll only be able to vaccinate a few percent of their citizens at most in the first couple months. The unvaccinated majority will still remain vulnerable to getting infected. A growing number of coronavirus vaccines are showing robust protection against becoming sick. But it’s also possible for people to spread the virus without even knowing they’re infected because they experience only mild symptoms or none at all. Scientists don’t yet know if the vaccines also block the transmission of the coronavirus. So for the time being, even vaccinated people will need to wear masks, avoid indoor crowds, and so on. Once enough people get vaccinated, it will become very difficult for the coronavirus to find vulnerable people to infect. Depending on how quickly we as a society achieve that goal, life might start approaching something like normal by the fall 2021.

- If I’ve been vaccinated, do I still need to wear a mask? Yes, but not forever. The two vaccines that will potentially get authorized this month clearly protect people from getting sick with Covid-19. But the clinical trials that delivered these results were not designed to determine whether vaccinated people could still spread the coronavirus without developing symptoms. That remains a possibility. We know that people who are naturally infected by the coronavirus can spread it while they’re not experiencing any cough or other symptoms. Researchers will be intensely studying this question as the vaccines roll out. In the meantime, even vaccinated people will need to think of themselves as possible spreaders.

- Will it hurt? What are the side effects? The Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine is delivered as a shot in the arm, like other typical vaccines. The injection won’t be any different from ones you’ve gotten before. Tens of thousands of people have already received the vaccines, and none of them have reported any serious health problems. But some of them have felt short-lived discomfort, including aches and flu-like symptoms that typically last a day. It’s possible that people may need to plan to take a day off work or school after the second shot. While these experiences aren’t pleasant, they are a good sign: they are the result of your own immune system encountering the vaccine and mounting a potent response that will provide long-lasting immunity.

- Will mRNA vaccines change my genes? No. The vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer use a genetic molecule to prime the immune system. That molecule, known as mRNA, is eventually destroyed by the body. The mRNA is packaged in an oily bubble that can fuse to a cell, allowing the molecule to slip in. The cell uses the mRNA to make proteins from the coronavirus, which can stimulate the immune system. At any moment, each of our cells may contain hundreds of thousands of mRNA molecules, which they produce in order to make proteins of their own. Once those proteins are made, our cells then shred the mRNA with special enzymes. The mRNA molecules our cells make can only survive a matter of minutes. The mRNA in vaccines is engineered to withstand the cell’s enzymes a bit longer, so that the cells can make extra virus proteins and prompt a stronger immune response. But the mRNA can only last for a few days at most before they are destroyed.

So when Moderna said recently that its first 20 million would go to the United States, Canadian politicians were accused of letting their country lose its place. It wasn’t widely known that as a condition for receiving U.S. financial support, Moderna had promised Americans its first doses.

Erin O’Toole, the Conservative leader of Canada’s Parliament, introduced a motion requiring the government to post fulfillment dates for its orders, saying that citizens “deserve to know when they can expect each vaccine type.”

Doses may be promised, but production is not guaranteed

Even if other promising candidates, like Johnson & Johnson’s, soon get approval and take pressure off Pfizer and Moderna, there’s no guarantee the companies will be able to satisfy their commitments next year.

“People think, just because we’ve demonstrated in Phase 3 clinical trials that we have safe and effective vaccines, that the spigots are about to be turned completely on,” said Dr. Richard Hatchett, head of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness, one of the global nonprofits leading the Covax program with the W.H.O. “The challenges of scaling up manufacturing are significant, and they are fraught.”

[ad_2]

Source link