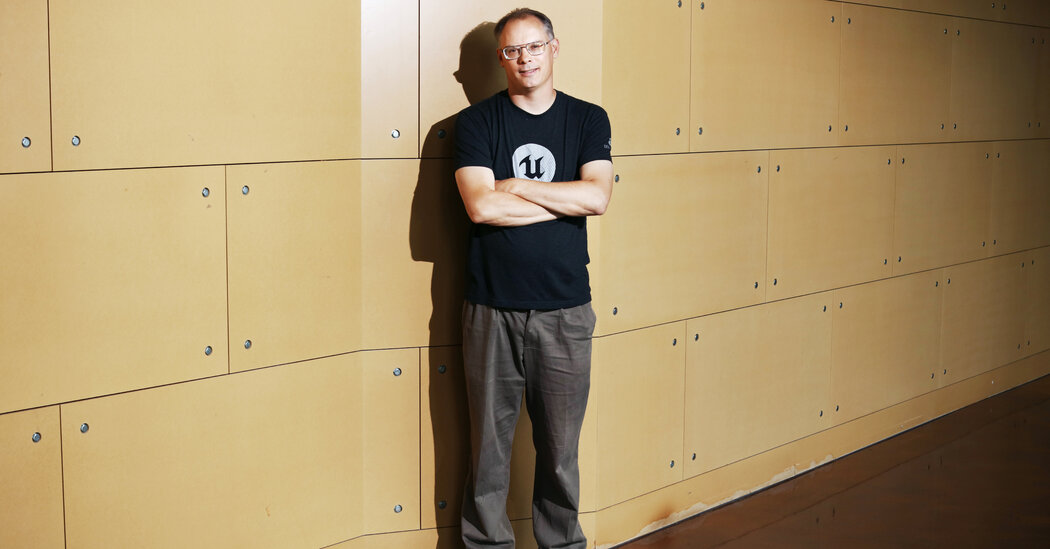

SAN FRANCISCO — Tim Sweeney, chief executive and founder of the video game maker Epic Games, has antagonized the world’s most powerful technology giants since at least 2016.

That year, Mr. Sweeney, a self-described computer nerd with a slightly nervous energy, lashed out in an op-ed against Microsoft, saying it was attempting “sneaky maneuvers” to dominate personal computer games. He also knocked Facebook’s Oculus Rift app store as “disappointing” for not being as “open” as it claimed.

In 2018, Mr. Sweeney went at it again. He launched Fortnite, Epic’s popular video game, outside Google’s Play Store to bypass its app store fees, which he called a “tax” and “disproportionate.” And in January at an industry conference, he declared that “undue power has accrued to many of the participants who are not at the core of the industry.”

His mission to rein in the power of the tech companies has now reached a fever pitch. Mr. Sweeney is preparing for a protracted legal battle after Apple and Google banned Fortnite, which is played by more than 350 million people, from their stores this month for trying to get around its payment systems. In response, Epic sued both companies, accusing them of violating antitrust laws by forcing developers to use those payment systems.

Mr. Sweeney’s yearslong public crusade against the tech Goliaths suggests that the issue is not something he will easily drop. People close to him said the fight was not about money or ego. Instead, they said, it is firmly about principle.

“He sees a vision of the world that is fair and open,” said Bradley Twohig, a venture capitalist at Lightspeed Venture Partners, which has invested in Epic.

Bruce Stein, chief executive of the esports start-up aXiomatic and an investor in Epic, said, “He was principled before he had the money to not be principled.”

How deeply Mr. Sweeney feels about tech power will be key as the fight with Apple and Google escalates. On Monday, a federal judge in the U.S. District Court of Northern California temporarily blocked Apple from cutting off support for an Epic software development tool called Unreal Engine. Mr. Sweeney had said that if Unreal Engine were cut off, it would be an “existential threat” to his company’s $17 billion business. The judge, who did not require Apple to bring Fortnite back to the App Store, will rule again on the matter next month.

In an interview last month, Mr. Sweeney, 49, said the stakes of the antitrust investigations into tech giants like Apple and Google were no smaller than the future of humanity. “Otherwise you have these corporations who control all commerce and all speech,” he said. He declined to be interviewed for this article, citing the active lawsuits, but has written on Twitter that he is “fighting for open platforms and policy changes equally benefiting all developers.”

“I don’t think we are going to be swayed unless we get what we think is right,” Adam Sussman, Epic’s president, said in an interview on Monday. “We will always sacrifice short term for long term.”

Other developers have embraced Epic’s cause. Spotify, the music streaming app, and Match Group, the maker of dating apps like Tinder, have released statements applauding Epic’s moves. In a legal brief on Sunday, Epic also outlined Microsoft’s support for it.

But to many others, Mr. Sweeney faces an uphill battle. In conversations with a dozen of Epic’s investors and former executives, as well as with deal makers and analysts in the gaming industry, many said that while they supported Mr. Sweeney’s stance, few expected him to prevail in all of his demands against Apple and Google.

“It’s a herculean uphill battle for them to beat Apple in court,” said Dan Ives, an analyst with Wedbush Securities, because Epic violated the terms of the App Store.

Asked for comment, Apple referred on Monday to its latest legal filing, in which it said Epic’s “‘emergency’ is entirely of Epic’s own making.” Google said it would “welcome the opportunity to continue our discussions with Epic and bring Fortnite back to Google Play.”

Mr. Sweeney, who grew up in Potomac, Md., and whose father worked for the Defense Mapping Agency, got into technology as a child. At age 9, he learned to code on an Apple II computer. In 1991, as a college student, he started Potomac Computer Systems, selling games on floppy disks via mail from his parents’ basement.

He eventually dropped out of the University of Maryland, where he had studied mechanical engineering. In 1992, he changed his company’s name to Epic MegaGames, then later dropped “Mega” and moved the start-up to North Carolina.

Epic, now based in Cary, N.C., began licensing its tools for graphics and game development — such as Unreal Engine — to other companies. That became a steady source of income, smoothing out the hits-or-bust nature of the games business.

In Epic’s early days, Mr. Sweeney was an awkward, quirky developer with a renegade streak who spent every waking hour writing code, investors and former colleagues said.

But he did get some use out of his Ferraris. “Having a fancy car is an excellent hobby when you’re a workaholic,” Mr. Sweeney said in an interview posted to YouTube in 2008. “Even if you don’t have any free time, you can still drive to work.”

By then, Mr. Sweeney had shown his stubborn streak. When Silicon Knights, a game development company, sued Epic in 2007 over Unreal Engine’s licensing, Epic spent five years and millions in legal costs to win the suit rather than settle.

Over the years, Mr. Sweeney also worked diligently to keep control of Epic, which is privately held. In 2012, when Epic considered selling itself, it found two options: It could sell a majority stake in its operations to Warner Bros. for roughly $800 million, or sell a minority stake for the same valuation to Tencent, the Chinese internet company, a person with knowledge of the discussions said.

Even though the Warner plan had more potential business advantages, Epic went with Tencent, which kept Mr. Sweeney in control.

His antagonism toward the big tech platforms began a few years later when Epic started building Fortnite, a battle royale-style fighting game that later expanded into a more creative mode where players could build their own games and challenges.

“We wanted to build online games and have a direct relationship with our customers,” Mr. Sweeney said in the July interview. He added that he had discovered that the fees from the app stores meant that Apple and Google could sometimes make more money on a game than its creators.

“That’s totally unjust,” he said. “That shows the market is out of control.”

Epic began work on its own app store, which it introduced in 2018. Epic’s store charges a 12 percent fee when a developer sells its wares through the store, compared with Google’s and Apple’s 30 percent cuts. After Epic created its games store, a competitor, Steam, lowered its fees from 30 percent to 20 percent for the biggest sellers.

In 2017, Fortnite became a runaway hit. Investors swarmed, and Epic raised more than $3 billion in funding from backers including Sony, KKR, BlackRock and Fidelity. Even with all the new investors, Mr. Sweeney maintained majority control, allowing him to focus on the long term.

“When you invest in Epic, you are signing up for a different journey,” Mr. Stein of aXiomatic said. “One that is focused on the gamer audience, not on quarterly results.”

Mr. Sweeney’s ambitions go beyond the gaming world. Fortnite is not just a place to fight virtual battles, the idea goes, but also a potential home for the “metaverse,” a digital universe for all kinds of interactions and experiences. In April, nearly 28 million people attended a Travis Scott concert inside Fortnite.

Mr. Sweeney has backed down once from a fight with a tech giant. In April, two years after releasing Fortnite outside the Google Play Store, Epic agreed to offer the game through the store. It said it was doing so because users were encountering “scary, repetitive security pop-ups” to download and update the app outside the Play Store.

Even so, Mr. Sweeney was not afraid to thumb his nose at the Apple App Store and Google Play Store. This month, Epic started encouraging Fortnite’s mobile-app users to pay it directly, rather than through Apple or Google. That violated Apple’s and Google’s rules that they handle all such app payments so they can collect their 30 percent commission.

In response, Apple banned Fortnite from its store; Google later did the same. Epic was ready. It rallied its fans around the hashtag #FreeFortnite and published a video satirizing Apple’s famous “1984” ad, which had portrayed Apple as the underdog. The parody included a villain wearing the same sunglasses as Apple’s chief executive, Tim Cook.

On Sunday, Epic hosted a #FreeFortnite gaming contest offering anti-Apple hats and digital avatars as prizes. And Mr. Sweeney? He also played along.

[ad_2]

Source link