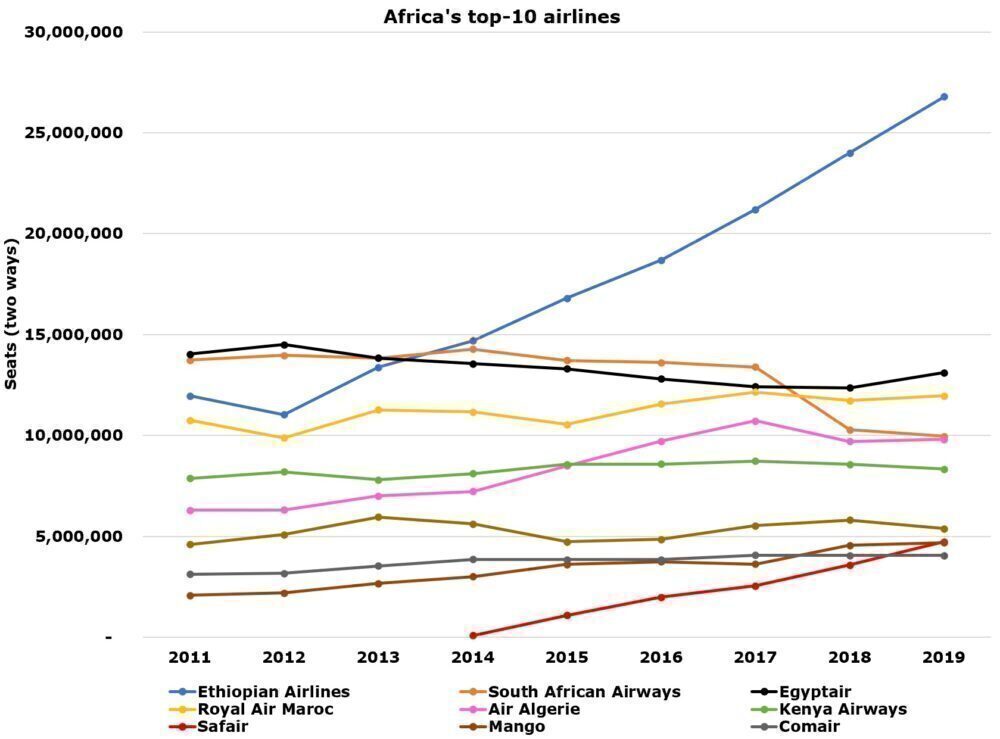

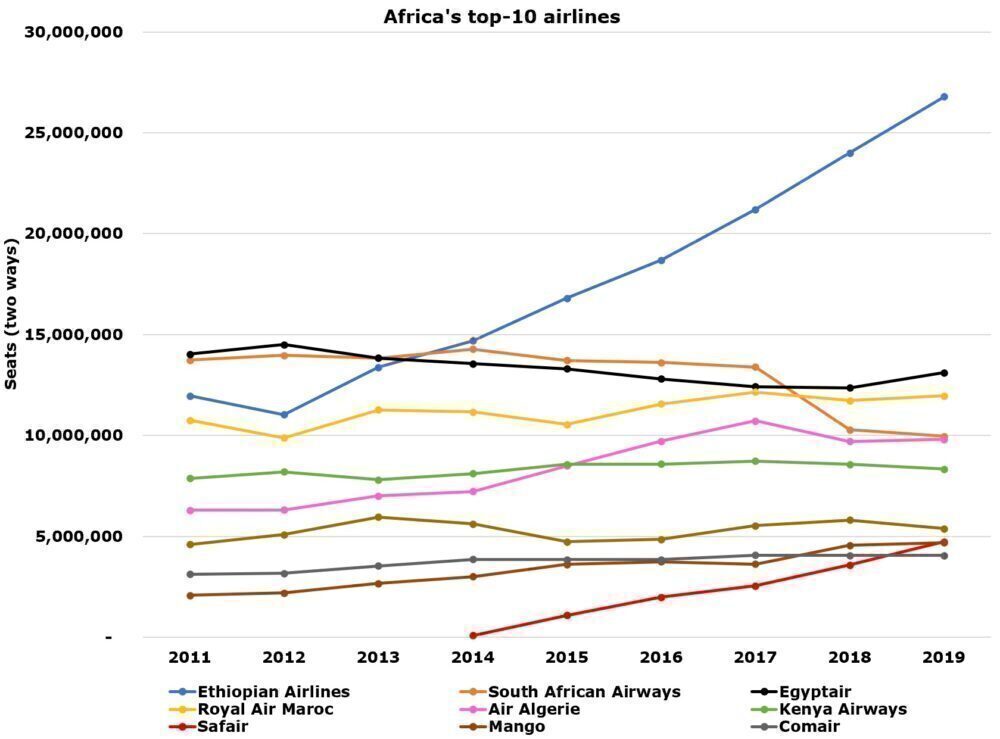

Ethiopian Airlines is by far Africa’s leading airline and is twice the size of number-two. It has grown faster than the rest of Africa’s top-10 put together. It has a wildly mixed fleet, although this isn’t really surprising given the carrier’s strategy. What has driven its success?

Ethiopian Airlines grew extremely quickly between 2011 and 2019, with the full-service carrier more than doubling in size. It added nearly 15 million seats – over five million more than all of the others in the top-10 combined.

It cemented its position as Africa’s leading airline, helped by significant cuts at others, notably South African Airways because of its continued major challenges, and generally minimal growth across the board.

Ethiopian Airlines ended 2019 with 26.8 million seats – over twice as many as for number-two, EgyptAir. Despite being 100% government-owned, Ethiopian largely owes its success to:

- The government letting it operate commercially (very unusual in Africa)

- The effectiveness of its management (unusual in Africa)

- Its geographic position

- Lack of suitable competitors, especially for intra-Africa

- Generally strict approach of keeping competitors out

Extremely mixed fleet

Ethiopian Airlines has an extremely mixed fleet. According to the airline, it currently has 128 aircraft:

- 28 Dash-8-400s

- 19 B787-8s

- 18 B737-800s

- 16 A350-900s

- 10 B737-700s

- Eight B787-9s

- Four B777-300ERs

- Four B737 MAX 8s (grounded)

- Six B777-200LRs

- Three B767-300ERs

And on the freight side:

- 10 B777-200Fs

- Two B737-800Fs

It also has a further 41 on order across B737 MAXs, A350-900s, B787-9s, and Dash-8-400s.

Its new aircraft should help to somewhat rationalize its fleet, but don’t expect many changes. Ethiopian Airlines’ highly complex fleet is often the case for hub-and-spoke operators with many different sector lengths and widely varying levels of demand on its routes.

Enormously about connections

Using its well-positioned hub on clear and increasingly important traffic flows, Ethiopian Airlines is a highly-coordinated hub carrier. It mainly focuses on connecting the Middle East, Asia, Europe, and North America with East, South, Central, and West Africa, along with connecting:

- Major cities in East and Southern Africa with North, Central, and West Africa

- North and Central Africa to East, West, and Southern Africa

- Sao Paulo, Brazil, to Asia generally and China in particular

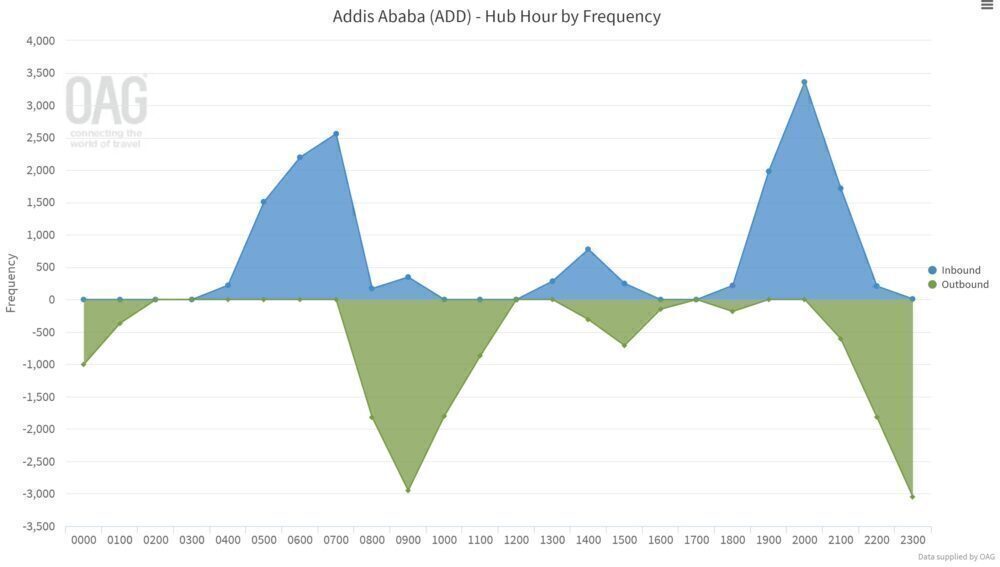

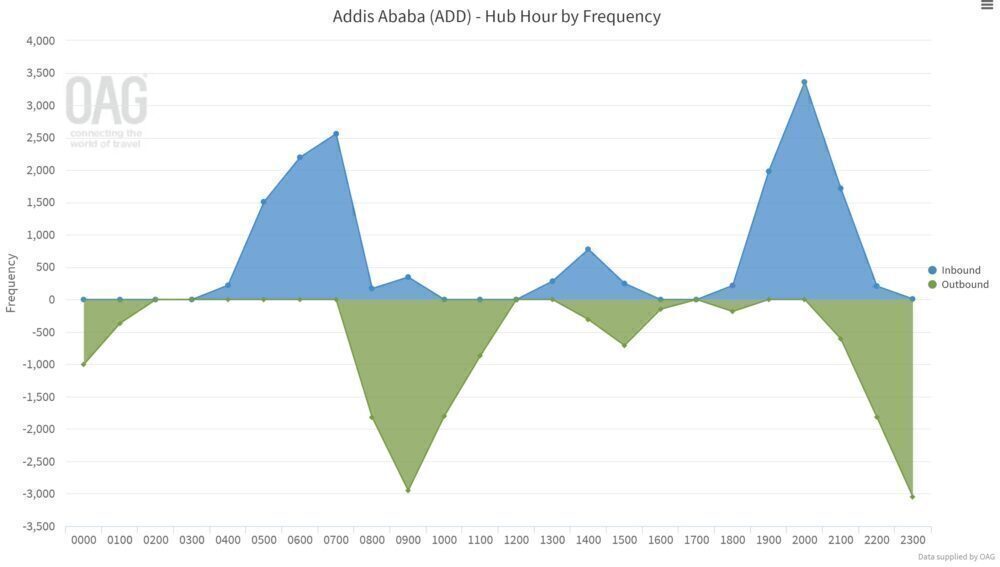

For this, it has two real waves of international flights each day, as shown below, with the arrivals and departure banks of each having a broadly different direction of flights.

Two main waves, but a third growing

The arrivals bank in wave one, from around 0500 to 0800, involves arrivals from across:

- Europe

- The Middle East

- Asia

- North America

- Various cities in Central, North, East, and Southern Africa

Aircraft then depart across Africa between around 0800-1000. Aircraft on long day-return flights, such as to Cape Town, naturally leave earlier in the departure bank, in this case at 0815. They then arrive back later in the next main arrivals wave, in Cape Town’s case at 2200.

The flights in the departure bank of wave one form the arrivals bank of wave two, which is almost fully 1900-2100 but extending to 2200.

The departures bank of wave two is primarily 2200-0030, which sees aircraft depart to:

- The Middle East

- Europe

- Asia

- North America

- Some major cities in North, Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa

Then they return to form the arrivals of wave one, although this shows a problem from having only two main waves. To maximizefeed, aircraft can be on the ground at their destination for many hours, such as Manchester: arriving at 0620 and departing at 2030.

Ethiopian’s fleet not too surprising

Many hub-and-spoke operators – and full-service carriers generally – have often asked ‘what aircraft do we need to operate X route?’ In contrast, low-cost carriers have asked, ‘I have Y aircraft, so where can I fly them?’ This is clearly seen at Ethiopian Airlines.

Of course, greater fleet complexity, while more costly, also enables greater right-sizing between demand and supply to ensure an efficient aircraft is used. This goes to the heart of the hub-and-spoke model. As connectivity and demand increase, both from passengers and freight, more and more city-pairs should be able to use larger and more cost-efficient aircraft.

This is strongly demonstrated with Ethiopian Airlines, with 75% of its seats and half of its flights this summer by widebodies.

What are your thoughts about the success of Ethiopian Airlines? Comment below!