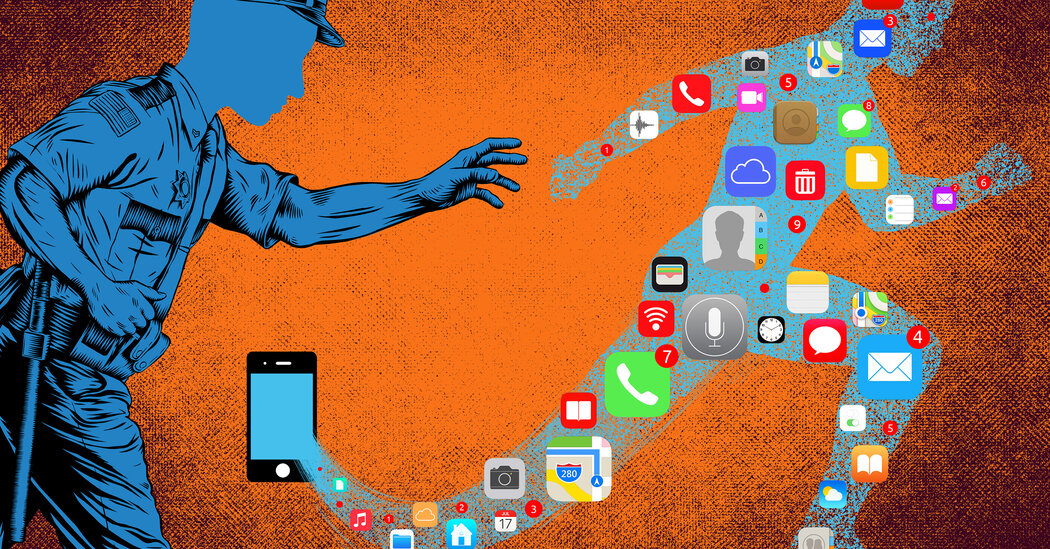

The companies frequently turn over data to the police that customers store on the companies’ servers. But all iPhones and many newer Android phones now come encrypted — a layer of security that generally requires a customer’s passcode to defeat. Apple and Google have refused to create a way in for law enforcement, arguing that criminals and authoritarian governments would exploit such a “back door.”

The dispute flared up after the mass shootings in San Bernardino, Calif., in 2015 and in Pensacola, Fla., last year. The F.B.I. couldn’t get into the killers’ iPhones, and Apple refused to help. But both spats quickly sputtered after the bureau broke into the phones.

Phone-hacking tools “have served as a kind of a safety valve for the encryption debate,” said Riana Pfefferkorn, a Stanford University researcher who studies encryption policy.

Yet the police have continued to demand an easier way in. “Instead of saying, ‘We are unable to get into devices,’ they now say, ‘We are unable to get into these devices expeditiously,’” Ms. Pfefferkorn said.

Congress is considering legislation that would effectively force Apple and Google to create a back door for law enforcement. The bill, proposed in June by three Republican senators, remains in the Senate Judiciary Committee, but lobbyists on both sides believe another test case could prompt action.

Phone-hacking tools typically exploit security flaws to remove a phone’s limit on passcode attempts and then enter passcodes until the phone unlocks. Because of all the possible combinations, a six-digit iPhone passcode takes on average about 11 hours to guess, while a 10-digit code takes 12.5 years.

The tools mostly come from Grayshift, an Atlanta company co-founded by a former Apple engineer, and Cellebrite, an Israeli unit of Japan’s Sun Corporation. Their flagship tools cost roughly $9,000 to $18,000, plus $3,500 to $15,000 in annual licensing fees, according to invoices obtained by Upturn.

[ad_2]

Source link