Swarm’s new network of satellites is intended to provide low-bandwidth, low-power connectivity to “Internet of Things” devices all over the world, and the company just announced how much its technology will actually cost. A $119 board will be sold to be integrated with new products, so while your home security camera won’t get it, it might be invaluable for a beehive monitor deep in an orchard or gunshot detection platform in a protected wildlife reserve.

The Swarm board is about the size of a pack of gum, and provides a constant connection at the kind of data rate and power requirement that IoT devices need — which is to say, low. After all, things like barometric pressure monitors, seismic activity detectors, and vehicles that operate far from cellular coverage just send and receive a handful of bytes now and then.

Connecting those to legacy geosynchronous satellite networks is possible, of course, but also expensive, bulky, and power-hungry. Swarm aims to offer a similar service for a tenth of the price; The company’s basic data plan provides up to 750 packets per month, with each packet up to 200 bytes. Not a lot, but it’s more than enough for many applications.

It’s important to keep costs down and connectivity up in growing industries like precision agriculture and smart maritime and logistics work. Being able to check in hourly from anywhere in the world for five bucks a month is a no brainer for many companies that otherwise might have to go blind or pay quite a bit more for a traditional satellite link.

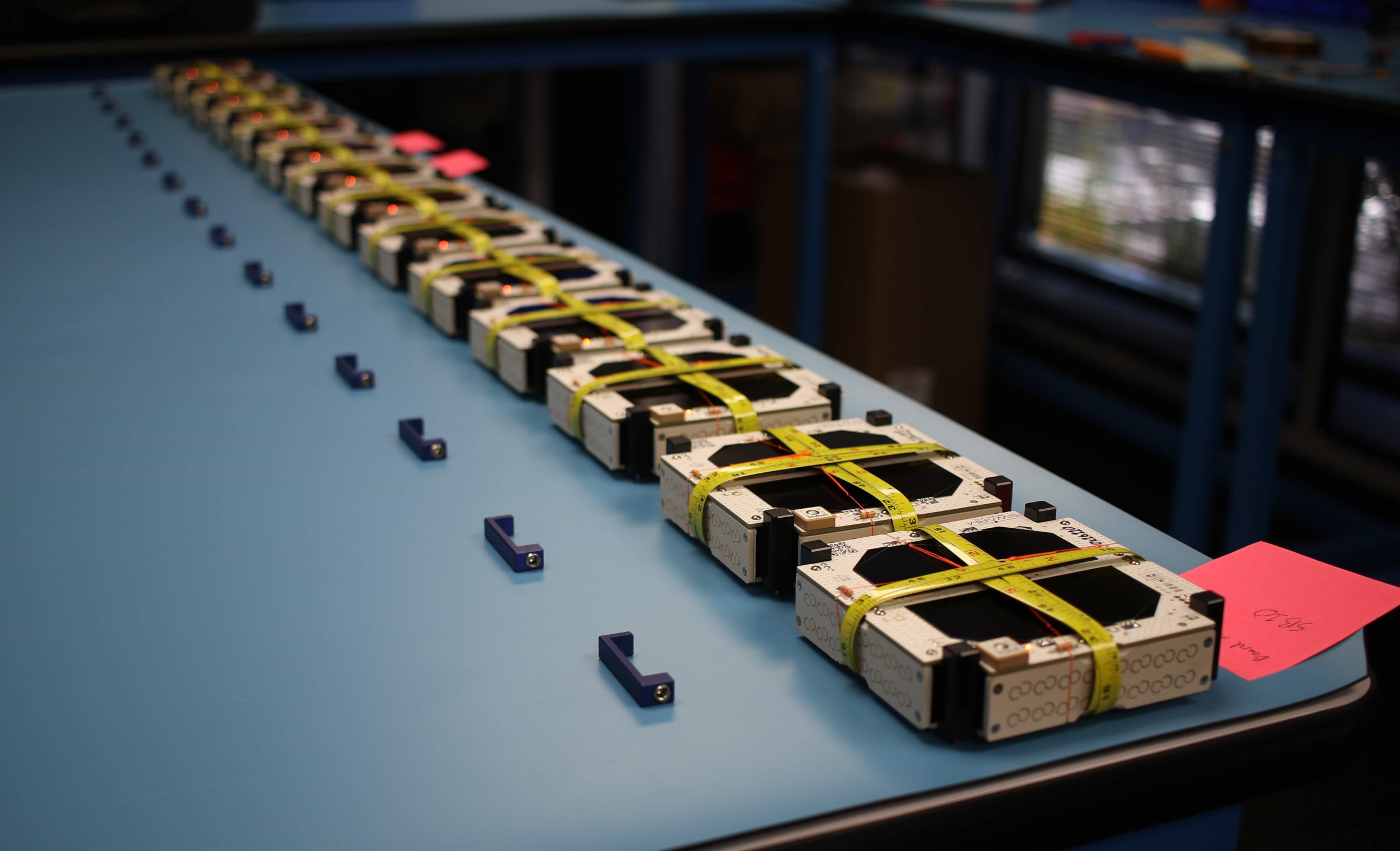

It’s not just the Swarm chip that’s small — the satellites themselves are too. So much so that they attracted unwanted attention from the FCC, which worried that the company’s “SpaceBEEs” were too small to be effectively tracked from the ground. Fortunately Swarm got that all cleared up last year and sent its first dozen up earlier this month.

Right now the company has 12 of a planned 150 satellite constellation in orbit, so it’s still proving out its network with early access and pilot projects. That affects covered areas and traffic limits, but the company expects the full set to be in orbit by mid-2021.