This article is part of the On Tech newsletter. You can sign up here to receive it weekdays.

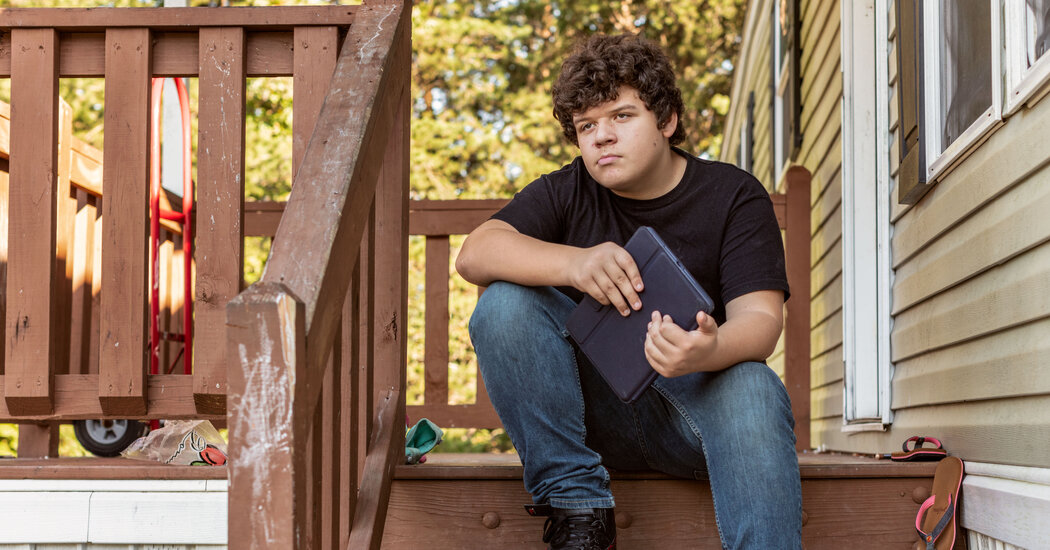

This period of remote schooling for so many families has made painfully clear the glaring gaps between those who have internet access and those who don’t. But some students also can’t access online classes because a surge in demand for laptops has left many schools and families struggling to find the computers they need.

I spoke with my colleague Kellen Browning, who wrote this week about the burdens from this other digital divide.

Shira: How are schools coping with the lack of available laptops?

Kellen: It’s stressful. Some school districts still haven’t realized how scarce laptops are right now. Others have had to jump on any computer that becomes available.

At the Bonneville School District in eastern Idaho, administrators said they were essentially told by Dell in September that if they placed an order right away, the district could get a couple thousand devices by November. But if they waited, computers might not arrive until February or so. Bonneville administrators scrambled to put together the funding for an order, because they felt it was too important to wait.

Did you find school districts or families with effective workarounds for students who don’t have computers?

There is a district in North Carolina that opened “learning centers” on school property with Wi-Fi and devices, and small numbers of students could occasionally attend. A teacher in that district was able to get a hold of some tablets through the church where he was a pastor. A lot of places were asking for donated devices or they were refurbishing older computers. Some districts were printing out course materials as a last resort. None of this is ideal.

Could schools have done something different to avoid this laptop desert?

Schools could have built stockpiles ahead of time, but the underlying problem is gaps between the rich and poor, and between well-funded and poorly funded school districts. Schools with fewer resources face a double whammy because their students are less likely to have computers and internet access at home, and the districts tend to have less money to buy enough laptops for them.

On the bright side, I guess, a lot of people said they believed the pandemic exposed the problems of this digital divide and created urgency to do something about it.

Is there urgency to close these digital gaps? Remote learning is (hopefully) temporary.

Yes, remote learning may be temporary, but access to reliable internet and devices at home will be essential for kids even when in-person classes resume.

I was struck by a conversation I had with Ashley Wright, a teacher at Pike County Elementary in Zebulon, Ga. She said that she brought an iPad to school one day and showed students Google Earth, which helped them grasp the enormity of the world they live in. For her it drove home the importance of devices and the internet as tools to help understand the world.

If you don’t already get this newsletter in your inbox, please sign up here.

The seven words you can never say at Google*

It’s not a good sign when companies bend over backward not to step on legal land mines.

That’s what I thought when I read my colleague Dai Wakabayashi’s surreal article about the ways Google employees are trained not to say or write anything that might suggest the company is an illegal monopoly.

Workers are taught that Google doesn’t “crush,” “kill,” “hurt” or “block” the competition. All could be evidence that the company is breaking antitrust laws. One person interviewing for an executive position got a bad mark for asking about antitrust implications of a potential merger in a follow-up email to Google’s chief executive. Lawyers are copied on even innocuous emails as a way of excluding the messages from prying regulators, Dai reported.

This all seems like oddball antics of a bizarre company. But when companies cross the line between sensible legal caution and this level of hyper vigilance, it can be a red flag.

It was not a good sign when Amazon for years used aggressive tactics to avoid applying sales tax on many U.S. purchases. To make it appear that Amazon wasn’t legally subject to sales tax laws, The Wall Street Journal reported that staff members had to seek permission to enter certain states and were instructed to use special business cards in California that listed their employer as “Amazon Digital Services,” a subsidiary, rather than Amazon itself. (Amazon now collects sales tax on products it sells.)

ProPublica recently wrote about a company that hires at-home customer service representatives and strictly polices the words used to describe the work to emphasize that workers are contractors rather than employees. The workers don’t schedule “hours” but “intervals.” Call-center reps are not “working,” they are “servicing,” ProPublica explained.

All companies worry about legal liability. When you have to go to extreme lengths like requiring words that defy the English language, using fake business cards and writing “ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGE” on a team’s bug fixes, something has gone awry.

*The headline is a reference to a George Carlin comedy routine. Do not look this up if children are nearby.

Before we go …

Hugs to this

“PLEASE STOP CALLING THE POLICE DEPARTMENT ABOUT THIS SUNFISH!!” This ocean sunfish is so weird looking that residents of a Massachusetts town called emergency services about it. A lot. (The fish is VERY WEIRD and it spits at people, so … yeah, I’m suspicious, too.)

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think of this newsletter and what else you’d like us to explore. You can reach us at ontech@nytimes.com.

If you don’t already get this newsletter in your inbox, please sign up here.

[ad_2]

Source link