Johnson & Johnson is testing a coronavirus vaccine known as JNJ-78436735 or Ad26.COV2.S. Results from a clinical trial are expected in January.

Janssen Pharmaceutica, a Belgium-based division of Johnson & Johnson, is developing the vaccine in collaboration with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

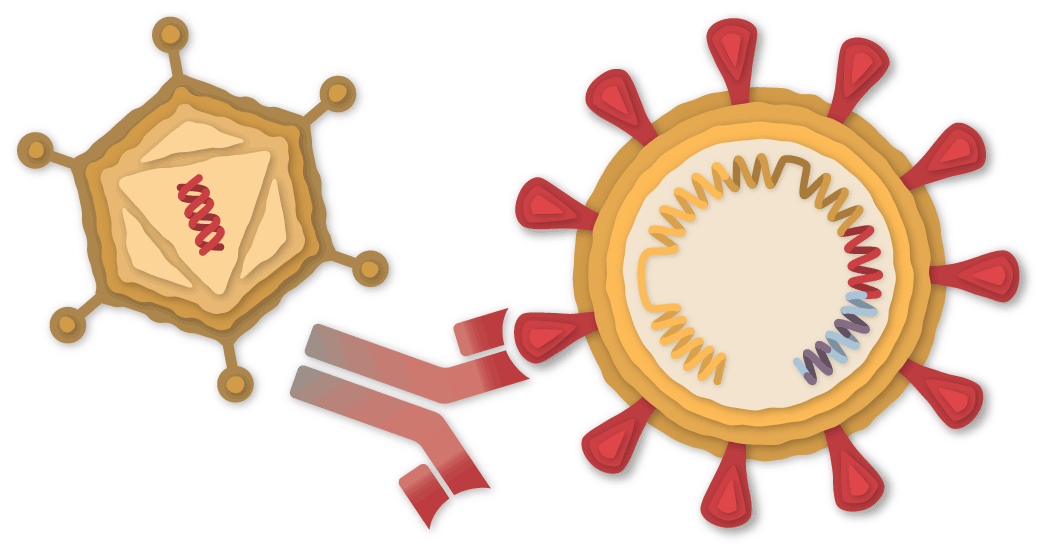

A Piece of the Coronavirus

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is studded with proteins that it uses to enter human cells. These so-called spike proteins make a tempting target for potential vaccines and treatments.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine is based on the virus’s genetic instructions for building the spike protein. But unlike the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, which store the instructions in single-stranded RNA, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine uses double-stranded DNA.

DNA Inside an Adenovirus

The researchers added the gene for the coronavirus spike protein to another virus called Adenovirus 26. Adenoviruses are common viruses that typically cause colds or flu-like symptoms. The Johnson & Johnson team used a modified adenovirus that can enter cells but can’t replicate inside them or cause illness.

Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine comes out of decades of research on adenovirus-based vaccines. In July, the first one was approved for general use — a vaccine for Ebola, also made by Johnson & Johnson. The company is also running trials on adenovirus-based vaccines for other diseases, including H.I.V. and Zika. Some other coronavirus vaccines are also based on adenoviruses, such as the one developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca using a chimpanzee adenovirus.

Adenovirus-based vaccines for Covid-19 are more rugged than mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna. DNA is not as fragile as RNA, and the adenovirus’s tough protein coat helps protect the genetic material inside. As a result, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine can be refrigerated for up to three months at 36–46°F (2–8°C).

Entering a Cell

After the vaccine is injected into a person’s arm, the adenoviruses bump into cells and latch onto proteins on their surface. The cell engulfs the virus in a bubble and pulls it inside. Once inside, the adenovirus escapes from the bubble and travels to the nucleus, the chamber where the cell’s DNA is stored.

Virus engulfed

in a bubble

Virus engulfed

in a bubble

Virus engulfed

in a bubble

The adenovirus pushes its DNA into the nucleus. The adenovirus is engineered so it can’t make copies of itself, but the gene for the coronavirus spike protein can be read by the cell and copied into a molecule called messenger RNA, or mRNA.

Building Spike Proteins

The mRNA leaves the nucleus, and the cell’s molecules read its sequence and begin assembling spike proteins.

Three spike

proteins combine

Spikes

and protein

fragments

Displaying

spike protein

fragments

Three spike

proteins combine

Spikes

and protein

fragments

Displaying

spike protein

fragments

Three spike

proteins combine

Spikes

and protein

fragments

Displaying

spike protein

fragments

Three spike

proteins combine

Spikes

and protein

fragments

Displaying

spike protein

fragments

Three spike

proteins combine

Spikes

and protein

fragments

Displaying

spike protein

fragments

Three spike

proteins combine

Spikes

and protein

fragments

Displaying

spike protein

fragments

Three spike

proteins combine

Spikes

and protein

fragments

Displaying

spike protein

fragments

Some of the spike proteins produced by the cell form spikes that migrate to its surface and stick out their tips. The vaccinated cells also break up some of the proteins into fragments, which they present on their surface. These protruding spikes and spike protein fragments can then be recognized by the immune system.

The adenovirus also provokes the immune system by switching on the cell’s alarm systems. The cell sends out warning signals to activate immune cells nearby. By raising this alarm, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine causes the immune system to react more strongly to the spike proteins.

Spotting the Intruder

When a vaccinated cell dies, the debris contains spike proteins and protein fragments that can then be taken up by a type of immune cell called an antigen-presenting cell.

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

The cell presents fragments of the spike protein on its surface. When other cells called helper T-cells detect these fragments, the helper T-cells can raise the alarm and help marshal other immune cells to fight the infection.

Making Antibodies

Other immune cells, called B-cells, may bump into the coronavirus spikes on the surface of vaccinated cells, or free-floating spike protein fragments. A few of the B-cells may be able to lock onto the spike proteins. If these B-cells are then activated by helper T-cells, they will start to proliferate and pour out antibodies that target the spike protein.

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface

proteins

Matching

surface

proteins

Matching

surface

proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Matching

surface proteins

Stopping the Virus

The antibodies can latch onto coronavirus spikes, mark the virus for destruction and prevent infection by blocking the spikes from attaching to other cells.

Killing Infected Cells

The antigen-presenting cells can also activate another type of immune cell called a killer T-cell to seek out and destroy any coronavirus-infected cells that display the spike protein fragments on their surfaces.

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning

to kill the

infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning

to kill the

infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning

to kill the

infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Presenting a

spike protein

fragment

Beginning to kill

the infected cell

Remembering the Virus

Johnson & Johnson is testing a single dose of the vaccine, unlike the two-dose coronavirus vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca. But because Johnson & Johnson’s Phase 3 trial results have not yet been released, researchers don’t know how well the vaccine might work, or how long its protection might last.

If the vaccine is effective, it’s possible that the number of antibodies and killer T-cells will drop in the months after vaccination. But the immune system also contains special cells called memory B-cells and memory T-cells that might retain information about the coronavirus for years or even decades.

Vaccine Timeline

January, 2020 Johnson & Johnson begins work on a coronavirus vaccine.

March Johnson & Johnson receives $456 million from the United States government to help develop and produce the vaccine.

July A Phase 1/2 trial begins. Unlike the clinical trials for other leading vaccines, the trial involves one dose, not two.

A dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.Michael Ciaglo/Getty Images

August The federal government agrees to pay Johnson & Johnson $1 billion for 100 million doses, if the vaccine is approved.

September Johnson & Johnson launches a Phase 3 trial.

Oct. 8 The European Union reaches a deal to obtain 200 million doses.

Oct. 12 The company pauses its Phase 3 trial to investigate an adverse reaction in a volunteer.

Oct. 23 The trial resumes.

Nov. 16 Johnson & Johnson announces a second Phase 3 trial to observe the effects of two doses of their vaccine, instead of just one.

Dec. 17 Johnson & Johnson announces its Phase 3 trial is fully enrolled, with around 45,000 participants.

January, 2021 Preliminary results from the Phase 3 trial are expected in January. The company is aiming to produce at least a billion doses in 2021.

February If trials show the vaccine is effective, the company could apply for emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration in February.

Sources: National Center for Biotechnology Information; Nature; Lynda Coughlan, University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Tracking the Coronavirus

[ad_2]

Source link