Luis von Ahn, an entrepreneur who has dedicated his career to scaling free education, has probably annoyed you more than once. In fact, you’ve likely been annoyed by his work dozens and maybe hundreds of times over the years.

A decade before he co-founded the whimsical and language-learning app Duolingo, one of the most popular education apps in the world with over 500 million downloads and 40 million active users, he was building the technology that would become CAPTCHA, those human-annoying but bot-preventing little tests that pop up when registering or logging in to popular internet services like email.

It may seem like a radical pivot, but in fact, the lessons of how to create useful security tests at scale for consumers would one day offer the core DNA for building one of the most successful edtech companies in the world. The immigrant entrepreneur would soon learn himself that crowdsourcing, language and a willingness to adapt and ignore critics could change the face of an industry forever.

CAPTCHA’ing a market

Von Ahn grew up in Guatemala City, where he saw firsthand the wretched state of public schools in impoverished countries. His mother spent most of her income sending him to “fancy private school” as he puts it, and he estimates she spent over $1 million on his education over his lifetime. The price tag weighed on him, and he knew he wanted to broaden access to education in the future.

After attending Duke as an undergrad, von Ahn was an enterprising first-year computer science Ph.D. student at top-ranked Carnegie Mellon University when he attended a talk by Yahoo’s chief scientist about 10 of Yahoo’s biggest headaches. One issue stood out: hackers were creating bots that register thousands of email addresses to send spam.

Inspired and full of immigrant grit, von Ahn and a team led by his then-adviser Manuel Blum created a nifty little test that could distinguish between bots and humans. The test, called a CAPTCHA, presented squiggly, ink-blotted words whenever a user tried to log in. Computer vision at the time couldn’t read the obscured text, but humans easily could — creating a useful signal. The deceptively simple test worked, so von Ahn, then a 20-something student, gave it to Yahoo for free, not understanding the value it would one day have.

Luis von Ahn, the inventor of CAPTCHA and reCAPTCHA, and co-founder of Duolingo. Image Credits: Duolingo

A fire was lit. With Yahoo as a distribution channel, CAPTCHA tests exploded in popularity, becoming an almost universally recognizable security checkpoint feature. At their peak, people spent 500,000 hours a day typing up to 200 million CAPTCHAs around the world. About 10% of the world’s population had recognized at least one word, von Ahn estimates.

For all the technology’s success, though, there was a downside. “During those 10 seconds while you’re typing in a CAPTCHA, your brain is doing something that computers can’t do, which is amazing,” von Ahn said. But the tests were annoying and pointless, so he wondered, “Could we get those 500,000 hours a day to do something useful for humanity?”

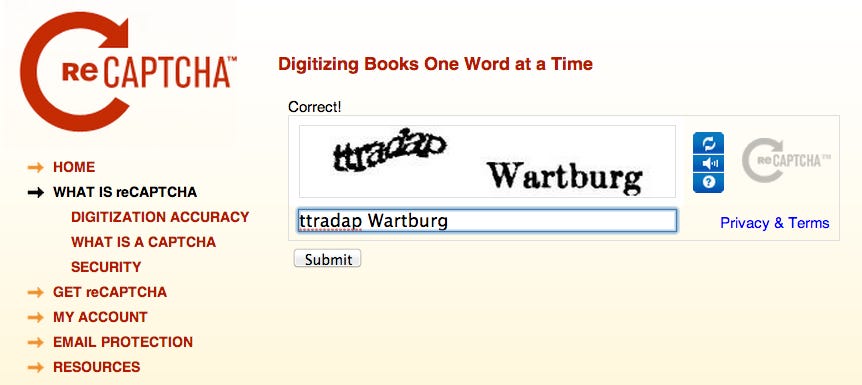

So in 2005, he launched reCAPTCHA. These new tests would have the same goal of CAPTCHA, but with a twist: the prompts would all be scans of books. Users would complete the security test while also helping to digitize books for the Internet Archive.

The early design of reCAPTCHA. Image Credits: Duolingo

This time, von Ahn knew his nifty idea was worth something. In 2009, he sold reCAPTCHA to Google, a transaction conducted just a year after the internet giant had purchased a license to one of his other research projects, a game focused on image labeling.

Luis von Ahn presenting about reCAPTCHA and CAPTCHA, two of his iconic inventions. Image Credits: Duolingo

The acquisition offered not just a monetary award (exact terms of the deal were not disclosed), but also suddenly garnered von Ahn serious clout in the industry just a few years after acquiring his Ph.D. Yet, instead of taking up tenure at the tech company, he stayed local in Pittsburgh and became a computer science professor at his alma mater.

Entering the world of education as a professor felt like an answer to his original dream of expanding access to education. What von Ahn didn’t know, though, was that his iconic work was simply foreshadowing. Carnegie Mellon, crowdsourced translation and even Google would all play a role in his next project as well, albeit in wildly different ways: incubation, failure and investment. For him, the success of two tools that used language as a barrier was the beginning of a long journey into discovering if, and how, language could instead be a bridge. It was an insight that would grow into a startup valued at $2.4 billion with the goal of making language learning fun: Duolingo.

Duolingo’s first words

In 2011, edtech startups such as Coursera and Codecademy were popping up — companies that today are valued as multibillion-dollar businesses. The rise of iPads and tablets in classrooms gave permission to founders who believed the future of education was on the internet. Enthusiasm was boiling, and virtual instruction felt like a nascent, but ambitious, place to bet on.