The C.D.C. has sent about $11 billion in relief funds to states and local jurisdictions for expanding coronavirus testing and contact tracing. A survey of state health departments by National Public Radio last month found they had roughly 37,000 contact tracers in place, with an additional 31,000 in reserve for when they would be needed. The work force — a mix of government employees, volunteers and contract workers hired by outside companies or nonprofit organizations — still falls short of the 100,000 people that the C.D.C. has recommended.

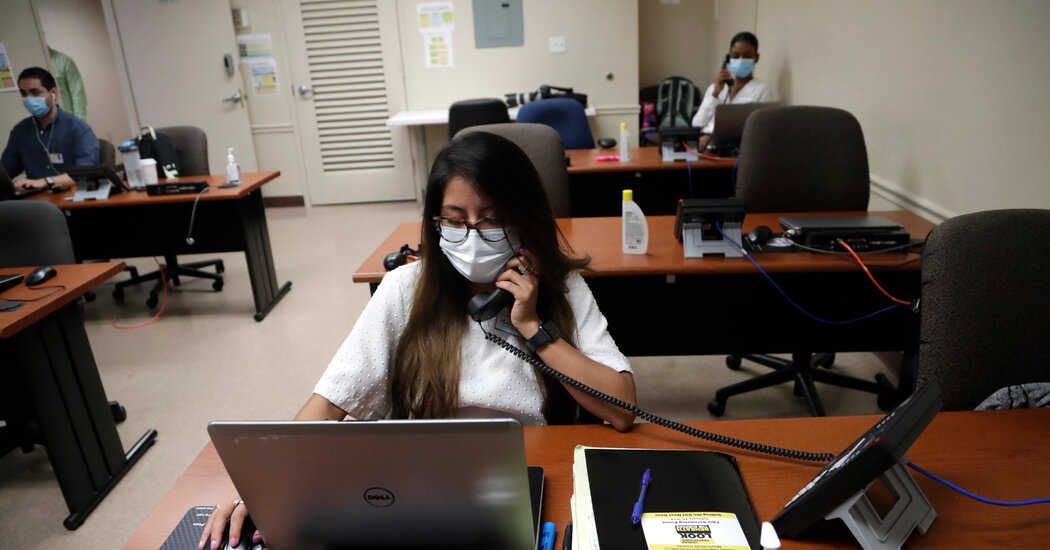

The contact tracers, whose training varies considerably in length and content depending on what state they are in, have struggled to keep up with the rising number of cases.

“The challenge is that we are not dealing with ones and twos,” said Fran Phillips, a deputy Secretary for Public Health for Maryland, a state that has largely kept the virus in check but still faces over 900 new cases daily. For every new case, there are several if not dozens of people to contact, especially in large cities, which further strains the system.

Contact tracing generally works best, public health experts say, when a disease is easily detected from its onset. That is often impossible with the coronavirus because a large percentage of those infected have no symptoms.

“When you have a situation in which there are so many people who are asymptomatic,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, at a recent Milken Institute event. “That makes that that much more difficult, which is the reason you wanted to get it from the beginning and nip it in the bud. Once you get what they call the logarithmic increase, then it becomes very difficult to do contact tracing. It’s not going well.”

Perhaps most harmful to the effort have been the persistent delays in getting the results of diagnostic tests. Often by the time an individual tests positive, it’s too late for the health care workers tracking that person to do anything.

“It’s a race against time,” Ms. Phillips said. “And if we have lost days and days of infectious period because we didn’t get a lab result back, that really diminishes our ability to do contact tracing.” In Maryland, like many states, some labs are taking as long as nine days to turn around results. “We are getting some assurances from national manufacturers this lag is short term,” she said. “I am not confident.”

[ad_2]

Source link