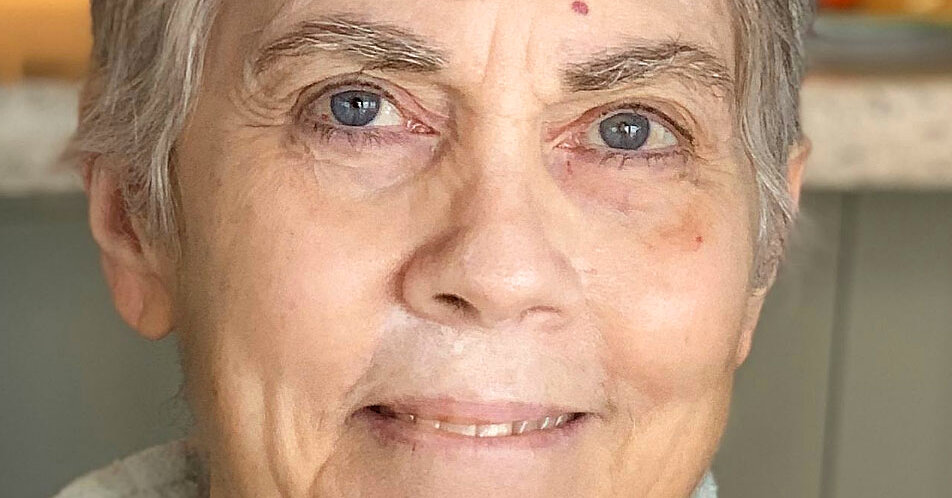

Ann Syrdal, a psychologist and computer science researcher who helped develop synthetic voices that sounded like women, laying the groundwork for such modern digital assistants as Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa, died on July 24 at her home in San Jose, Calif. She was 74.

Her daughter Kristen Lasky said the cause was cancer.

As a researcher at AT&T, Dr. Syrdal was part of a small community of scientists who began developing synthetic speech systems in the mid-1980s.

It was not an entirely new phenomenon; AT&T had unveiled one of the first synthetic voices, developed at its Bell Labs, at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. But more than 40 years later, despite increasingly powerful computers, speech synthesis was still relatively primitive.

“It just sounded robotic,” said Tom Gruber, who worked on synthetic speech systems in the early ’80s and went on to create the digital assistant that became Siri when Apple acquired it in 2010.

By 1990, companies like AT&T had started to deploy these new systems, allowing the hearing-impaired, for example, to generate synthetic speech for phone calls. The voices, though, typically sounded male.

That year, at the Bell Labs research center in Naperville, Ill., Dr. Syrdal developed a voice that sounded female — a much harder result to achieve, in part because so much of the previous engineering work had been done for male voices.

A decade later, she was part of a team at another AT&T lab, in Florham Park, N.J., that developed a system called Natural Voices. It became a standard-bearer for speech synthesis, featuring what Dr. Syrdal and others called “the first truly high quality female synthetic voice.”

In 2008, she was named a fellow of the Acoustical Society of America in recognition of her contributions to the rise of female speech synthesis, which is now a part of everyday life, thanks to Siri and Alexa.

“She was driven — and I mean driven — to optimize the quality of female voices,” said Juergen Schroeter, who ran the Natural Voices project.

Ann Kristen Syrdal was born on Dec. 13, 1945, in Minneapolis. Her parents, Richard and Marjorie (Paulson) Syrdal, had met while working at Minneapolis-Honeywell (now Honeywell), a heating company that grew into a technology giant in the years before World War II.

Her father, a physicist and engineer who developed vacuum tubes and other electrical technologies, died when Ann was 2. She was raised by her mother, a sales clerk at a Minneapolis department store.

When she enrolled at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Syrdal had not considered a science career. But when a psychology professor asked for her help with a lab experiment involving rats, she fell in love with lab work — even after realizing that she was severely allergic to rats.

She went on to earn both bachelor’s and Ph.D. degrees in psychology before being hired as a researcher by the Callier Center for Communication Disorders at the University of Texas at Dallas. In the early 1980s, after receiving a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health, she began exploring the mechanics of human speech at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

When she moved to Bell Labs, female voice synthesis was not a major area of research anywhere.

“They all thought a female voice was just a higher frequency version of the male voice, but that never works,” said H.S. Gopal, a speech researcher who worked alongside Dr. Syrdal during those years. “The male engineers just didn’t take female speech as seriously.”

At first, she improved on earlier efforts to build female voices, but in the late 1990s she joined a project that would help change the nature of speech synthesis. Rather than generating sounds from scratch, she and her colleagues developed ways of piecing together snippets of recorded human speech to form new words and new sentences on the fly. Dr. Syrdal oversaw the recordings.

The first recordings were made with six women, and when AT&T’s Natural Voices system topped an international competition for speech synthesizers in 1998 — an inflection point for this technology — it used a female voice.

Dr. Syrdal’s marriages to Scot O’Malley, Robert Lasky and Stephen Marcus ended in divorce. In addition to her daughter Kristen Lasky, she is survived by her partner of 23 years, Alistair Conkie, who worked alongside her at AT&T; a son, Sean O’Malley; another daughter, Barbara Evelyn Lasky; and eight grandchildren.

When Siri was integrated into Apple’s iPhone in 2011, both female and male voices were offered. “We did it because we wanted gender equality — and because it was possible,” Mr. Gruber said “People respond differently to different voices.”

In many countries, including the United States and Japan, female voices became the standard.

[ad_2]

Source link