[ad_1]

The twin-engine L-1011 was studied long before ETOPS reshaped aviation. Here’s why Lockheed’s TwinStar concept never flew.

The Lockheed L-1011 TriStar is remembered as one of the most technologically ambitious widebodies of its era. Its quiet cabin, advanced autoland capability, and distinctive S-duct made it one of the most recognizable airliners of the 1970s and 1980s.

But did you know that the TriStar began as a twin-engine concept?

In response to American Airlines’ 1966 requirement for a widebody domestic airliner, Southern California neighbors Lockheed and McDonnell Douglas jumped at the opportunity. While McDonnell Douglas began planning for what would eventually become the DC-10, Lockheed initially studied a twinjet design sometimes referred to in company materials as the CL-1011 (the “CL” stood for California Lockheed). The concept envisioned a short- to medium-haul twin-aisle aircraft powered by two high-bypass turbofans.

However, engine technology and regulatory constraints shaped the final configuration. Powerplant technology at the time was still maturing in terms of thrust and reliability. At the same time, the FAA’s “60-minute rule” limited twin-engine aircraft to routes within 60 minutes of a diversion airport. For airlines seeking maximum route flexibility, particularly overwater or transcontinental segments, this restriction was significant. Performance requirements for hot-and-high airports and shorter runways also weighed heavily.

Lockheed ultimately adopted a trijet configuration, adding the tail-mounted engine and S-duct that became the TriStar’s signature feature.

Revisiting the Twin: Early 1970s Studies

By the early 1970s, engine performance had improved and airline economics were shifting. Several sources indicate that Lockheed revisited the idea of a twin-engine derivative of the TriStar.

One study often referenced in enthusiast and archival discussions is the so-called CL-1600 or Model 1600. This appears to have explored removing the center engine from the existing TriStar airframe in pursuit of lower operating costs and simplified maintenance. Period accounts suggest the company believed significant cost reductions could be achieved by eliminating one engine and its associated systems.

Some secondary sources suggest that such concepts may have been informally discussed with carriers including Air Canada, though documentation of formal proposals remains limited in publicly accessible archives.

These studies did not progress to a launched program. Removing the tail engine from an aircraft structurally and aerodynamically optimized around a trijet configuration posed nontrivial engineering challenges.

It is worth mentioning that while Lockheed was conceptualizing a widebody twin-engine aircraft based on the TriStar, Airbus Industrie GIE (now Airbus) launched its A300 program. The A300, which closely resembled what a twin-engine TriStar would have looked like, first flew in October 1971 and was introduced into service with Air France in May 1974.

It would become the world’s first twin-engine, twin-aisle, widebody airliner, and featured a 2-4-2 seating configuration. It carried between 250-300 passengers, except up to nearly 370 passengers in a high-density configuration.

The L-1011-600: TwinStar or BiStar

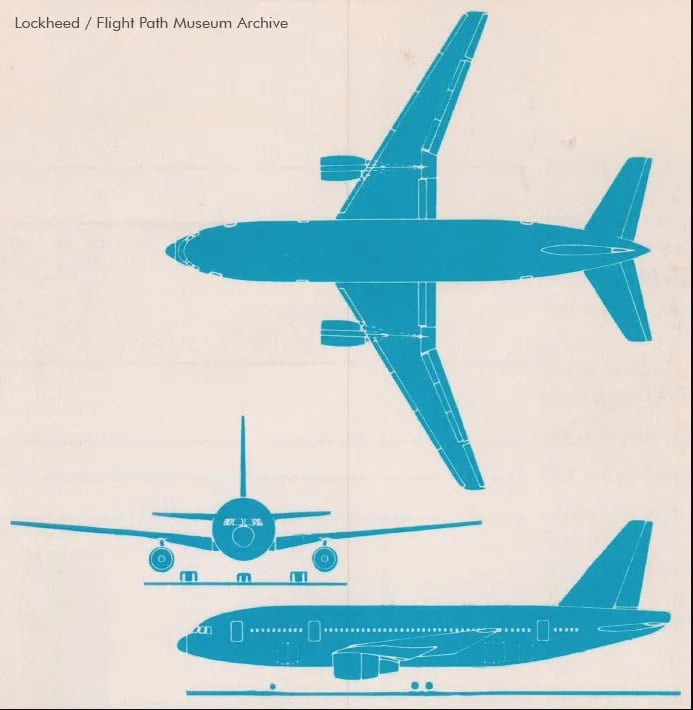

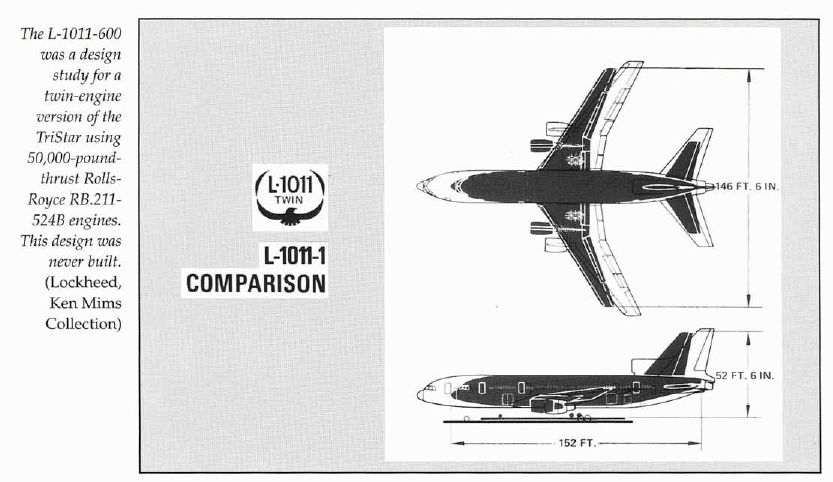

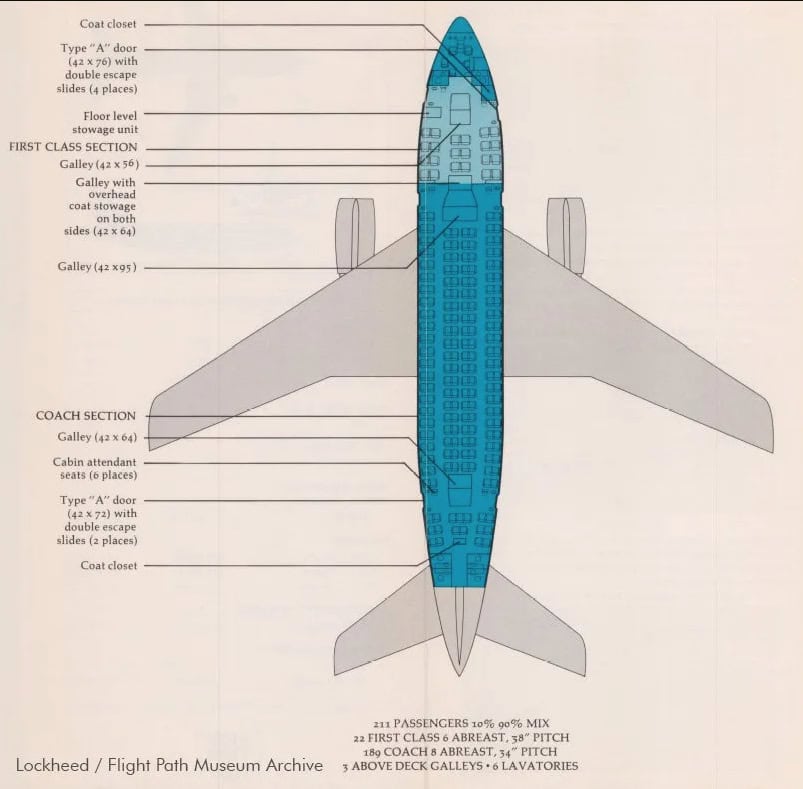

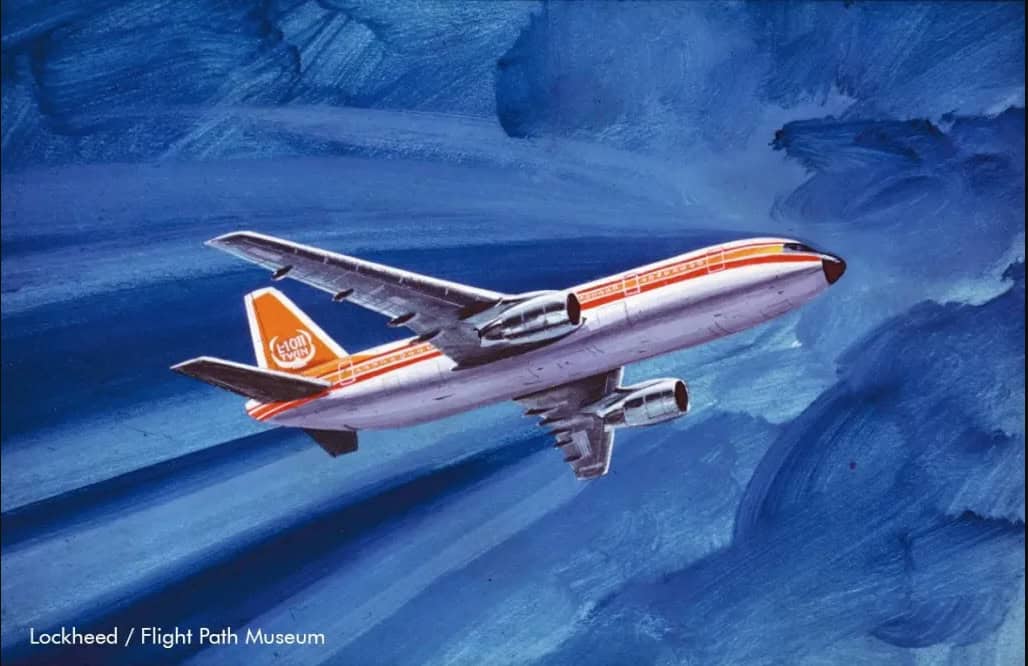

The most detailed twin-engine proposal associated with the TriStar is generally identified as the L-1011-600, sometimes referred to in period illustrations and later discussions as the “TwinStar” or “BiStar.”

Developed in the mid-1970s as part of an extended family of projected TriStar variants, the -600 was envisioned as a two-engine widebody optimized for shorter-haul routes. The only member of the L-1011 family to reach production was the Lockheed L-1011-500.

Available summaries of the -600 concept describe:

- Two underwing Rolls-Royce RB211-524 series engines in the 50,000-pound thrust class

- Elimination of the center tail engine

- Wing refinements tailored to twinjet operation

- Alternative vertical stabilizer studies, including a faired-over S-duct configuration and a more conventional twinjet-style fin

Proposed seating appears in most accounts as roughly 174 to 200 passengers, with a projected range in the neighborhood of 2,700 nautical miles. These figures should be understood as conceptual targets rather than certified specifications.

Artist renderings, three-view drawings, and desk models of the -600 circulated during the study period. However, no launch customer emerged, and there is no evidence that the design progressed beyond advanced study and marketing exploration.

So…Why Wasn’t it Built?

The reasons span two distinct eras of aviation development.

In the 1960s, regulatory restrictions (such as the FAA’s “60 minute rule”) and engine-performance realities favored three- and four-engine configurations for widebody aircraft. By the time engines such as the RB211-524 made high-capacity twinjets more viable, the competitive landscape had changed dramatically.

The Airbus A300 had entered service. The Boeing 767 was on the horizon as a clean-sheet twin optimized from inception for two-engine operation. Meanwhile, the TriStar program had faced significant delays and financial strain, including the well-documented impact of Rolls-Royce’s bankruptcy during engine development.

Airlines evaluating fleet decisions increasingly favored either proven existing types or entirely new-generation aircraft rather than heavily re-engineered variants. Lockheed ultimately chose to withdraw from the commercial airliner market and concentrate on military programs.

As a result, no twin-engine L-1011 was ever built or flown. No production variant was certificated. Later speculative designations and engine upgrade scenarios remain hypothetical and are not supported by documented Lockheed program launches.

The TriStar’s Legacy — And Its Last Flying Example

While the TwinStar never materialized, the TriStar itself left a remarkable legacy. It is a legacy we have covered extensively here at Avgeekery.

MORE ABOUT THE TRISTAR ON AVGEEKERY

Built between 1968 and 1984, Lockheed produced around 250 of the type, operated by carriers ranging from TWA and Delta to Cathay Pacific. Despite its advanced design, early engine supplier delays and associated cost overruns slowed entry to market and opened the door for competitors like the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 to win early sales. Lockheed never managed to reach the production volumes it needed for commercial profitability, ultimately withdrawing from the civilian aircraft industry.

That legacy continues in a unique way: one L-1011 remains airworthy today. The aircraft known as Stargazer — delivered in 1974 and originally operated by Air Canada — has been modified and operated as a peg-launched rocket mothership under companies now part of Northrop Grumman. As of 2026, Stargazer is the only L-1011 still flying and regularly performs missions out of Mojave Air and Space Port (MHV) in California, carrying Pegasus launch vehicles to altitude before release.

An Aviation What-If

The twin-engine L-1011 remains one of commercial aviation’s more intriguing “what might have been” stories.

The concept was born during a transitional moment in commercial aviation when widebody design philosophy was making the transition from tri- and quad-engine configurations toward the twinjet dominance that would define later decades. The studies were real. The renderings existed. The engineering was explored.

But the market moved faster than the concepts.

In the end, the TriStar’s third engine became its defining trait, and the twin remained a concept confined to drawings, desk models, and the margins of aviation history.

[ad_2]

Source link