[ad_1]

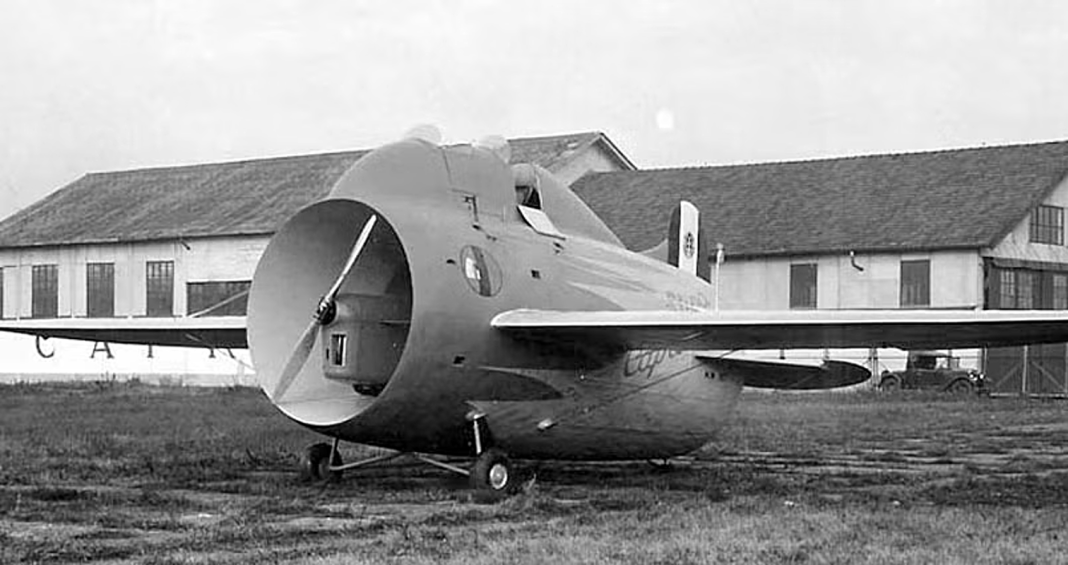

It would be difficult to find a more unique or odd-looking machine than the Italian Stipa-Caproni experimental aircraft. The plane, with its barrel or tube-shaped fuselage, was an experimental prototype model that made several successful flights. As strange as the Stipa-Caproni was, it might be possible to call it the first jet aircraft.

Design Based on Venturi Effect

In 1927, Italian aeronautical engineer Luigi Stipa was interested in improving aircraft performance. He devised the idea for his barrel-shaped aircraft based on his knowledge of the venturi effect. This thermodynamic principle states that the velocity of fluid will increase and its pressure will decrease when it flows through a constricted section of a pipe or tube.

Stipa speculated that a plane using the venturi effect in its design would be able to fly faster and with better performance than other aircraft flying at that time. He built a small-scale working model and tested it in a wind tunnel between 1928 and 1931. Based on these tests, he made some modifications to the design and concluded that it would be feasible to build and test a full-size model.

Support for Prototype from Italian Government

To do so, he needed to gain support for his design, which some called the Flying Barrel. In July 1933, he published his findings and data on the aircraft in the Italian Revista Aeronautica journal. Next, he contacted the Italian Ministry of Aviation, asking for help to build the prototype.

The 1930s was a time of much innovation and experimentation in aircraft designs. The Italian government was especially supportive of researching and testing new aircraft. General Luigi Crocco, director of the Air Ministry, saw potential in Stipa’s design and approved the project.

The next step was to build a working prototype. From the beginning, both the Air Ministry and Stipa only planned to use the prototype to test his concept for the aircraft. They knew there would likely not be any further development or additional models. Also, Stipa stated he felt the design would be best suited for larger aircraft such as bombers and cargo carriers.

Stipa-Caproni Had Unique Design Features

A key design feature was for the fuselage to have two large wooden rings and a series of smaller rings acting as spars. Horizontal ribs connected the rings, forming the basic shape. The large rings became attachment points for the wings and cockpit. Fabric covered the wings and fuselage. Metal braces and steel wires connected the wings to the fuselage.

Stipa positioned the tail so the slipstream from the tube would impact the control surfaces, hoping to improve flight performance and maneuverability. The aircraft had three landing gear, two in front and one in the rear.

Stipa and the engineers at Caproni installed a 120 HP de Haviland Gypsy III engine inside the tube and suspended it by stiff metal bars. The propellor was also inside the tube.

Stipa included the dimensions for his design in his initial report. It was to have a wingspan of 46.92 feet, a length of 19.8 feet, a height of 10.63 feet, and a wing area of 204.5 square feet.

He also planned for it to take off with a weight of 1763 pounds and require a takeoff and landing run of 590 feet.

First Flight of Stipa-Caproni Mostly Successful

They contracted with the Caproni aircraft manufacturing company from Milan Taliedo to build the prototype, and they completed it in October 1932. Two pilots took off in the Stipa-Caproni for the first time that same month. Their initial review was that it “flew without any major issues.”

During that first flight, the Flying Barrel experimental aircraft reached a maximum speed of 83 mph and reached an altitude of 9842 feet, although it took 40 minutes to get that high.

The pilots also reported the elevator, positioned in the slipstream, worked “excessively well,” producing sudden changes in pitch. Interestingly, they also said the rudder was very stiff, requiring considerable force to move the stick.

Doubts About the Future of Design

After the first one, they conducted several other test flights. So, with proof that the Stipa-Caproni could fly, the Italians had to decide what to do with it. After reviewing the flight data, the Air Ministry concluded that the aircraft “did not exhibit superiority over conventional designs.”

It was, in fact, slower than similar-sized aircraft. Stipa, however, had predicted this when he first designed it, repeating that it was better suited for larger aircraft. His initial report discussed a future with larger aircraft powered by multiple tube-shaped fuselages. He even included images of what these designs might look like.

Eventually, the Italian Air Ministry lost interest in the Stipa-Caproni experimental aircraft and scrapped the design. Later, in 1935, the French government showed some interest in the plan and purchased a license for it. They discussed building a two-engine variant. However, they gave up on the idea after some basic design work.

Similarities With Modern Turbofan Engines

Some have noticed that the tube design of the Stipa-Caproni was basically the same as that of turbofan engines on modern aircraft. The major difference is that modern engines have turbojets instead of piston-driven engines.

Aaron Spray of SimpleFlying.com has referred to the Stipa-Caproni as “nearly the first jet.” Others have called the aircraft a type of proto-jet engine, and there are similarities.

Possible Link to German Design

It is a bit ironic that several years after the Stipa-Caproni flew, Italy became an ally of Nazi Germany in the Second World War. During the war, the Germans deployed the first jet aircraft in combat, the Messerschmitt Me 262A Schwalbe. While Stipa was not involved with the Me 262, he suggested the Germans used his designs.

He went as far as claiming that the Germans stole his idea for the Stipa-Caproni and that the pulse engines on the V-1 flying bomb violated his in-tube propellor patent. According to some reports, he felt his work was overlooked and remained bitter about it for the rest of his life.

That wasn’t the end of the Stipa-Caproni story. In 1996, aviation enthusiast Guido Zuccoli began working on a small-scale replica. He passed away in 1997 before completing it. Another owner took on the project and finished it in 2001. One of the differences in this model was a different engine, a 72-hp Simonini racing engine. They made several flights in the aircraft. Today, it is on display at an exhibit in Toowoomba, Australia.

[ad_2]

Source link