The leader of the nation’s coronavirus testing efforts condemned Nevada’s health department on Friday for ordering nursing homes to discontinue two brands of government-issued rapid coronavirus tests that the state had found to be inaccurate.

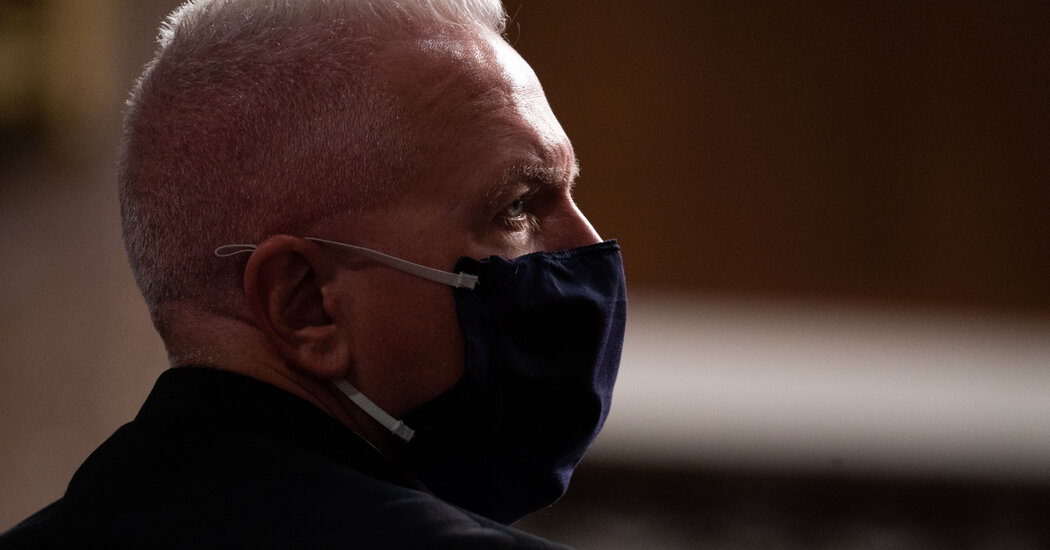

“Bottom line, the recommendations in the Nevada letter are unjustified and not scientifically valid,” Adm. Brett Giroir, an assistant secretary of Health and Human Services, said in a call with reporters on Friday. The state’s actions, he said, were “unwise, uninformed and unlawful” and could provoke unspecified swift punitive action from the federal government if not reversed.

The rapid tests, which were distributed to nursing homes around the country in August by the federal government, were supposed to address the months of delays and equipment shortages that had stymied laboratory-based tests.

“The important issue is to keep seniors safe,” Admiral Giroir said in an interview on Friday. Antigen tests, he added, were “lifesaving instruments” that had been called “godsends” by some nursing home representatives. About 40 percent of the country’s known Covid-19 deaths came from nursing homes, according to a New York Times analysis.

But Nevada officials had discovered a rash of false positives among two types of rapid tests, manufactured by Quidel and Becton, Dickinson and Company, that had been used in the state’s nursing homes. Both tests look for antigens, or bits of coronavirus proteins, and had been advertised as producing no false positives.

Among a sample of 39 positive test results collected from nursing homes across the state, 23 turned out to be false positives, the state reported. (The bulletin did not specify whether negative results from the antigen tests, of which there were thousands, had been confirmed, leaving the number of false negatives unknown.)

“I would consider that to be a significant number of false positives,” said Omai Garner, a clinical microbiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Admiral Giroir contended that such rates of false positives are to be expected, and are “actually an outstanding result.” No test is perfect, he said.

He also said that the federal government expected the state to promptly rescind its unilateral prohibition, which he described as a violation of the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act.

An Aug. 31 guidance from Admiral Giroir’s office stipulated that PREP Act coverage “preempts” states from blocking the use of coronavirus tests that have been authorized by the Food and Drug Administration on people in congregate settings, like nursing facilities.

What Nevada has done is “illegal,” he said. “They cannot supersede the PREP Act.”

The federal government’s formal response to Nevada’s health department, dated Oct. 8 and signed by Admiral Giroir, portrayed the state’s officials as scientifically incompetent and their actions as “improper” under federal law. “Your letter can only be based on a lack of knowledge or bias, and will endanger the lives of our most vulnerable,” Admiral Giroir wrote.

Should the state hold its ground, “there can be penalties from the federal side,” he said in an interview on Friday, but declined to provide details.

Nevada health officials did not respond to a request for comment. Both BD and Quidel issued statements saying they were pleased with Admiral Giroir’s response, and reaffirmed their confidence in their products’ performance.

Jennifer Nuzzo, a public health expert at Johns Hopkins University, described Giroir’s letter to Nevada as “unprecedented, in my view.”

“I’ve never witnessed anything like this in my entire life,” said Susan Butler-Wu, a clinical microbiologist at the University of Southern California. Nevada, she said, was “making a local determination that it’s causing too many problems for them. And they got a cease and desist.”

Tom Bollyky, director of the global health program and senior fellow for global health, economics and development at the Council on Foreign Relations, said Nevada could have legal grounds to push back against the federal government.

“They’re raising legitimate concerns about the accuracy of the test,” he said, noting that mandating certain types of tests wasn’t what the Act was written for: “It was meant to provide immunity against injury claims for vaccines and drugs.”

Should the matter proceed to litigation, or trigger similar actions from other states, however, nursing facilities could get caught in the middle of a tense dispute.

“Requiring that they navigate differences between federal and state mandates on testing — a crucial tactic — is one more burden during an already challenging time,” said Ruth Katz, senior vice president of policy at LeadingAge, an association of nonprofit providers of aging services.

Mr. Bollyky also noted being struck by the “acid” tone of the letter. “This is par for the course for 2020, but I can’t remember the last time, prior to 2020, I read a letter like this from an H.H.S. official to state health authorities,” he said.

“I did not mean to be disrespectful,” Admiral Giroir said in response to queries about the tone of the letter addressed to Nevada’s state officials. But he said he hoped the wording sent a clear and wide-reaching message that the federal government’s policies on testing — which he insists are “100 percent” backed by science — are not to be trifled with.

“I wanted to be clear to everyone, not just to Nevada,” he said, adding, “I think their decision is a wrong one.”

[ad_2]

Source link